The EMUI10 update has brought a new feature to Huawei devices, named “Quick Apps”, which turn out to be much more interesting than expected.

Artículo disponible en Español | Article disponible en Français

Huawei recently started rolling out the EMUI10 update on some devices, which, on top of bringing various improvements to the overall UI and system, has also brought an application named “Quick Apps”. While some might think that “Quick Apps” is something developed by Huawei themselves, it turns out the answer is a lot more complex and interesting than this. While Huawei is indeed involved in the development, it isn’t the only company to have them. For instance, a few days ago, various articles talked about how Google Protect had labelled Xiaomi’s Quick App as malware, blocking it. While it would seem nobody, or maybe only a few people, made the connection between Xiaomi’s “Quick Apps” and Huawei’s, it turns out that both are essentially the same.

The reason? Well, “Quick App” is a standard developed by an alliance of Chinese manufacturers, including, obviously, Huawei, Xiaomi, ZTE, Oppo and vivo, but also smaller, unknown or less popular brands such as Meizu, Gionee, Lenovo or Nubia. Originally, this alliance was composed of 9 manufactures, but now counts 12 in total, with the addition of OnePlus, HiSense and China Mobile Group Device Co., Ltd.. According to the information available, these manufacturers decided to form an alliance and create a common standard, the “Quick App”, with their goal being fighting WeChat, or, more precisely, the many integrated services available through WeChat. For those unaware, WeChat is a Chinese messaging application through which users can essentially do everything, be it buying food, paying purchases, booking tickets for transportation, etc. In a past article, we actually mentioned how some joke about if a company released a phone with only WeChat, this would be enough for many Chinese users. Regardless, on top of all these options, WeChat also has “integrated” applications, or mini applications, which don’t need to be installed on the device to be used, with these apps also covering a variety of needs, such as games.

At this point, some might have already realized what these “Quick Apps” are. With WeChat being able to satisfy the digital needs of most users, and their integrated mini applications covering the last few needs, users will not use the app store provided by the smartphone manufacturer, resulting in less traffic and downloads for these, which, in turn, means less revenue on digital downloads. It is also important to remind that Chinese users do not have access to Google services, meaning smartphones sold inside the Chinese market do not have the Google Play Store. Users rely on the manufacturers’ app store, or third-party app stores such as Tencent’s. Thus, “Quick Apps” aim to fight WeChat’s mini applications, by offering a similar solution which goes through the device manufacturer, ultimately benefiting this one.

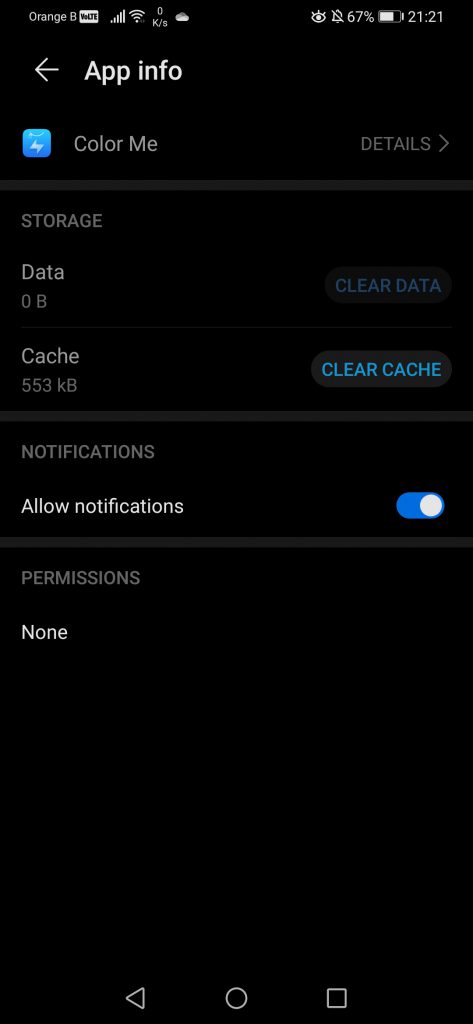

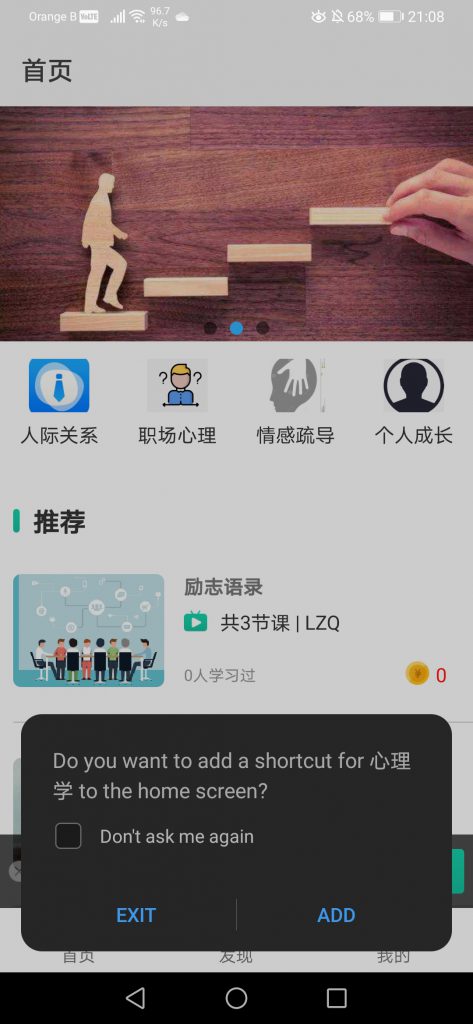

Overall, the goal of Quick App is to have small applications accessible without requiring an install, instead relying on being streamed. The user can easily add a shortcut on his phone too, so at the end of the day, these feel like full-blown apps, but need less space and can be obtained on demand. Sadly, it appears most of them require an internet connection to properly work. Some seem to do just fine, others launch but end up closing when trying to do anything, which is a downside if there’s no access to a stable and reliable connection. Furthermore, if the internet access was to go down at some point for an extended period of time, this could pose a problem to users relying on these quick apps, being unable to play games for instance. Quick Apps also supposedly use less space, which is both true and untrue. While the applications themselves don’t need to be installed on the device, the data produced by the user while interacting with these apps ends up taking storage space. For example, by the end of this article, our “Quick App Centre” used 134 MB of storage space on our phone, while a clean install of this app only takes 86 MB. One has to keep in mind that each individual application we tested would have taken anywhere between 40 to 60 MB for a regular install, so we do end up saving quite a lot of space overall.

If we now have a look at Huawei’s developer website, it is possible to learn quite a lot about these “Quick Apps”, such as the fact that the standard is supported by “12+ major Chinese mobile phone manufacturers”, which should be interpreted as more manufacturers might support them in the future. Furthermore, these 12 manufacturers cover 85%+ of the Chinese market and 1 billion devices, according to their website, a rather surprising number, as this essentially leaves out Samsung’s and Apple’s market share. It would be interesting if Samsung joined this program, although this is unlikely to happen. Ironically, one could point out how Chinese manufacturers do the best to accommodate Western users, while the contrary does not seem to be true. Huawei’s documentation also mentions that “at least four major Chinese manufacturers” will be deploying quick apps outside of China “within” 6 months. There’s no information on when this page was created, but we can assume it is very recent, on top of Huawei having just released “Quick Apps” with the EMUI10 update here in the Western world. Oppo also lists “Quick apps” in the help section of one of their international websites, and in vivo’s English developer documentation, one can find how to submit quick app games too. Ironically, this same vivo documentation mentions Oppo, showing how both companies seem to share some of their resources, with vivo and Oppo being owned by the same company, BBK Electronics (which also owns OnePlus). Regardless, this puts it at 4 major manufacturers, which are the only 4 having any real presence outside of China.

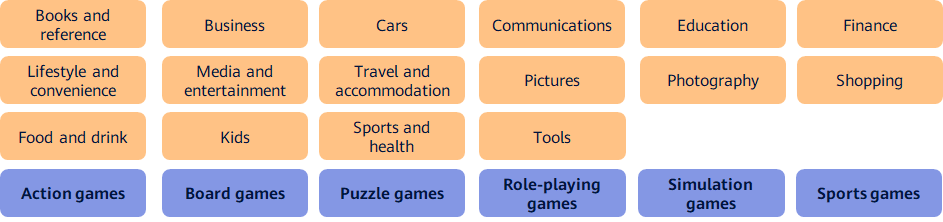

Lastly, the documentation provided by Huawei to getting started with Quick apps mentions this standard supports all “H5” apps and games, with “H5” essentially being HTML5 mobile-responsive websites (“H5” being the naming used in China), and covers 90% of all app and game categories. These apps supposedly only need the equivalent of 20% of the code of an Android app and can be easily developed and deployed in a few days.

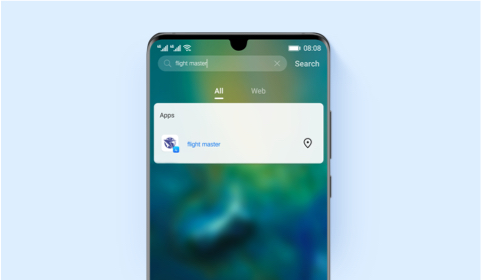

Huawei also mentions how integrated Quick Apps can be with the system overall, mentioning some of them can be added to their Assistant, be found via AppGallery or the Quick App Centre, have a shortcut added to the home screen so they behave exactly the same way as other installed applications or be found via their “Global search” function, although both the Assistant and this “Global search” compatibilities are still under development.

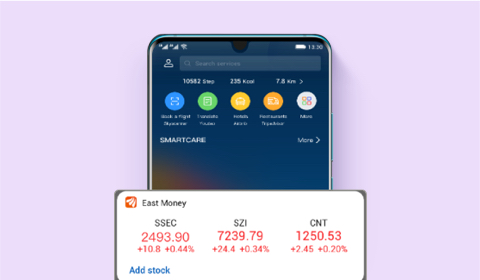

The more interesting feature here is the Huawei Assistant integration, as we noticed this a while back, when we wrote our overview of this application. The marketing material from the company included a screenshot with various cards displaying stocks and others, which we initially thought would be included cards users could pick at a later date.

It turns out these are specific Quick Apps one will be eventually able to add to the Assistant, and thus act as a “Smartcare” card, which opens quite a lot of possibilities in terms of customization.

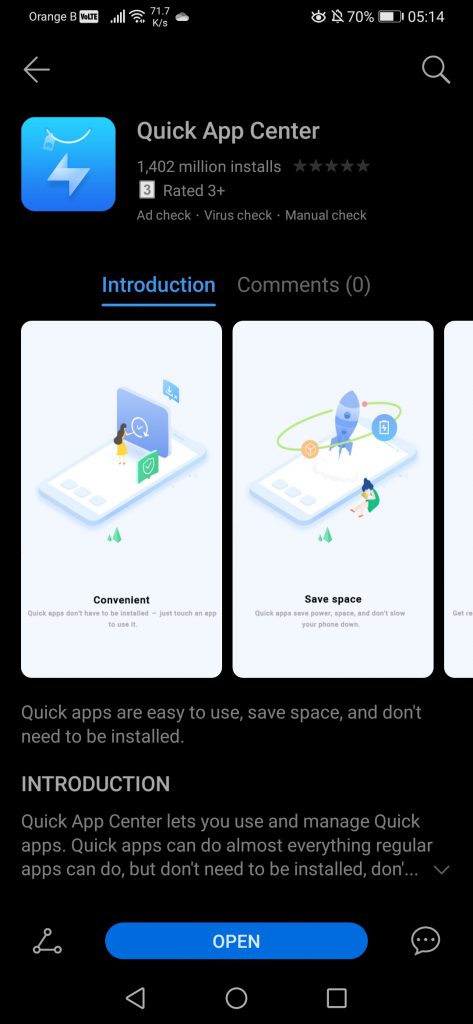

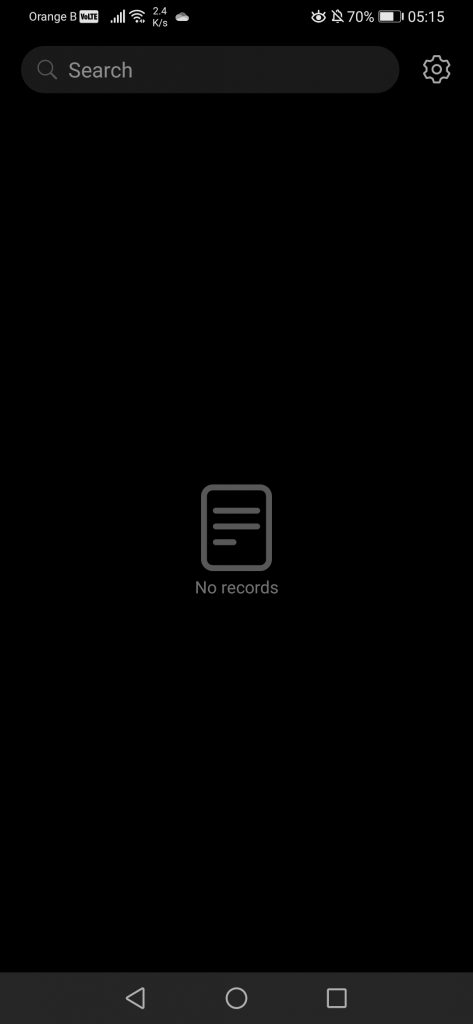

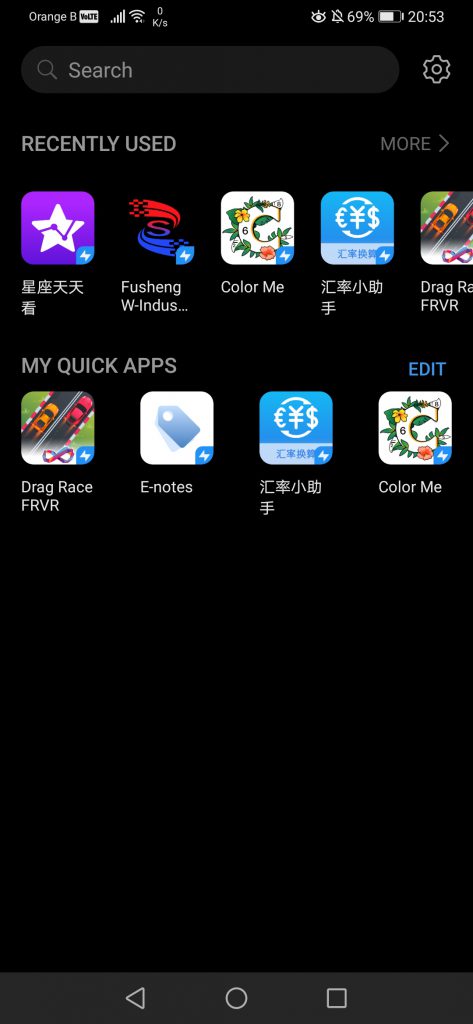

Now, after such a long introduction, let’s start and have a look at these “Quick Apps”. While they were added on AppGallery following the EMUI10 update, it would seem Huawei released them globally around that date, as it is possible to download them from AppGallery on a different device still on EMUI9.1. If integrated to AppGallery, the “Quick Apps” section can be found in the “Manager” tab. Taping on this one will bring up the typical license agreement form Huawei uses, as well as detail the permissions needed for this app to properly work. Once agreed, we’ll be welcomed by an empty page. Before proceeding further, we can add a shortcut for this section on our home screen, allowing us to access our quick apps faster, unless we decide to add shortcuts for them too.

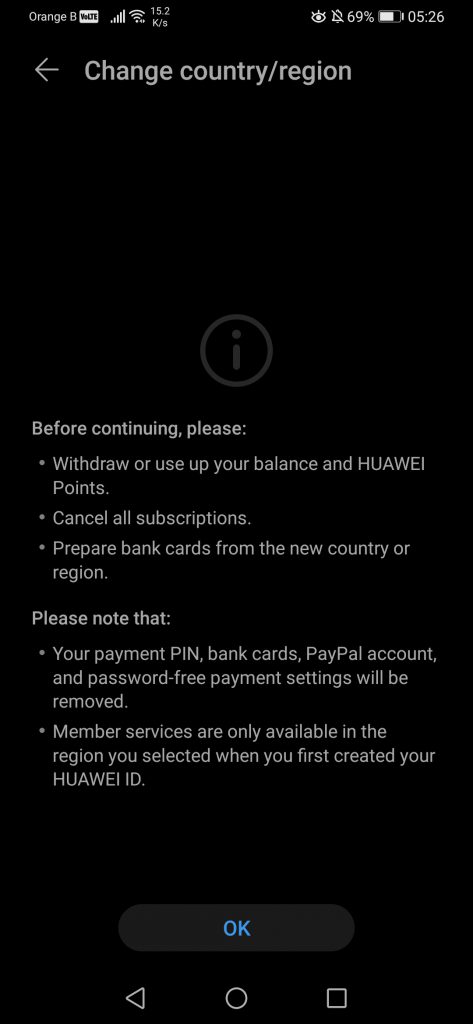

The settings don’t have anything special. As per usual, we are able to quickly access our Huawei ID (we’ve edited this one out for more privacy), add the “Quick Apps Centre” to the home screen, switch country, check for updates or see more details about this application. Switching country or region appears to not be a good idea, especially if one has Huawei Points in their wallet.

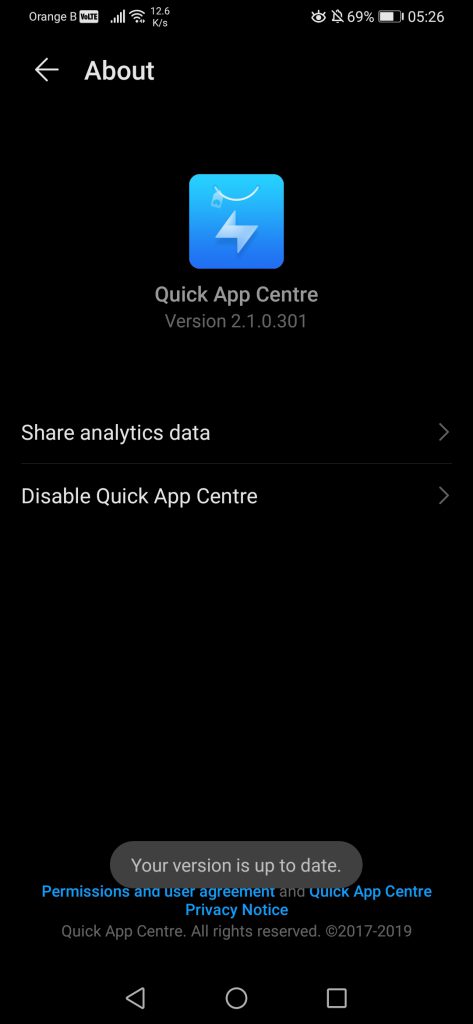

In the “About” section, we can disable sharing analytics data with the company or disable the “Quick App Centre” altogether. We would recommend disabling the “Share analytics data” option, as we would rather not share our data with any company if possible. Disabling the “Quick App Centre” also means deleting all the data linked to the Quick Apps we used, which makes sense, and would be the equivalent of uninstalling all the applications of a smartphone.

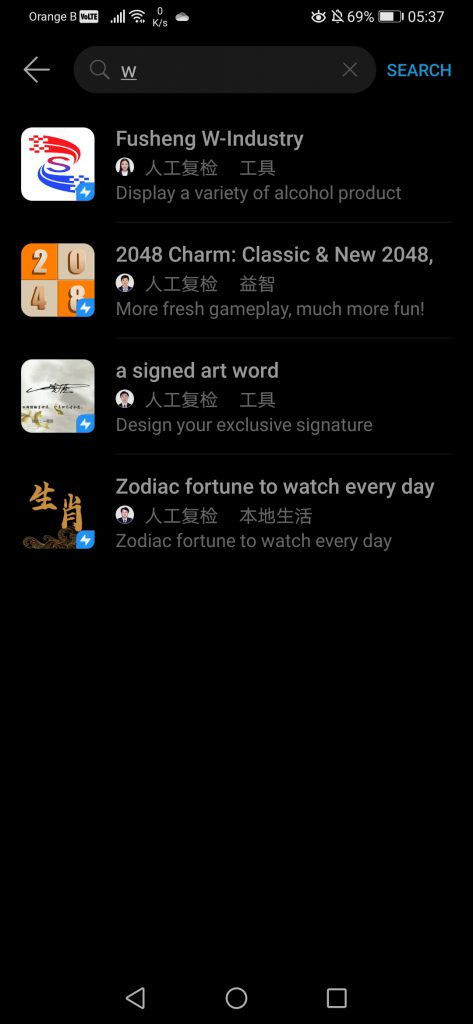

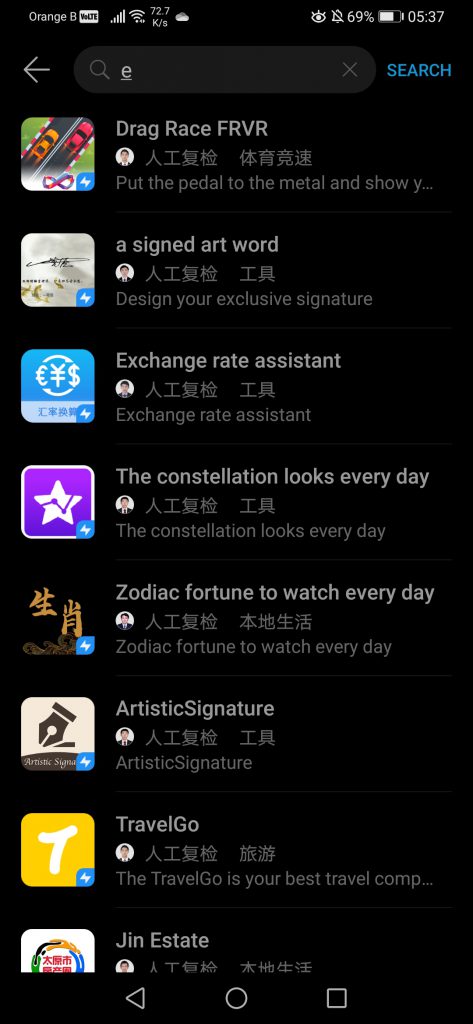

We’ve looked for a few quick apps, but currently, it appears most of them are in Chinese, making them useless to us. By typing each letter of the alphabet, we’ve managed to find a few applications and test them. Choice is very limited for now, although Huawei mentions in the search results that more quick apps will be made available “soon”:

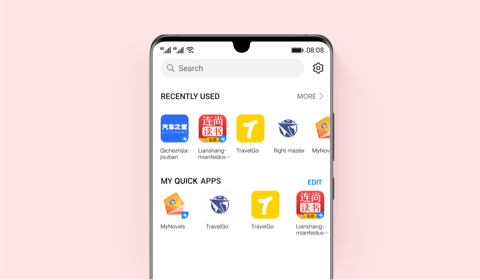

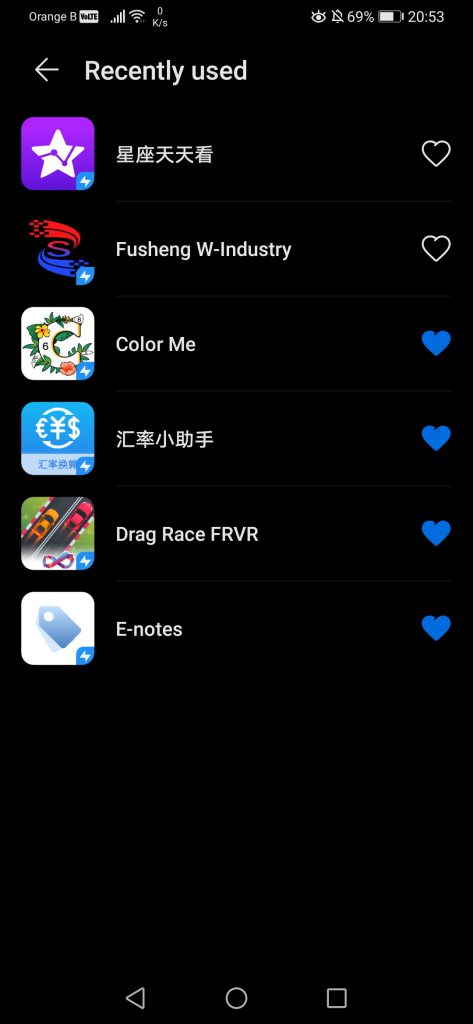

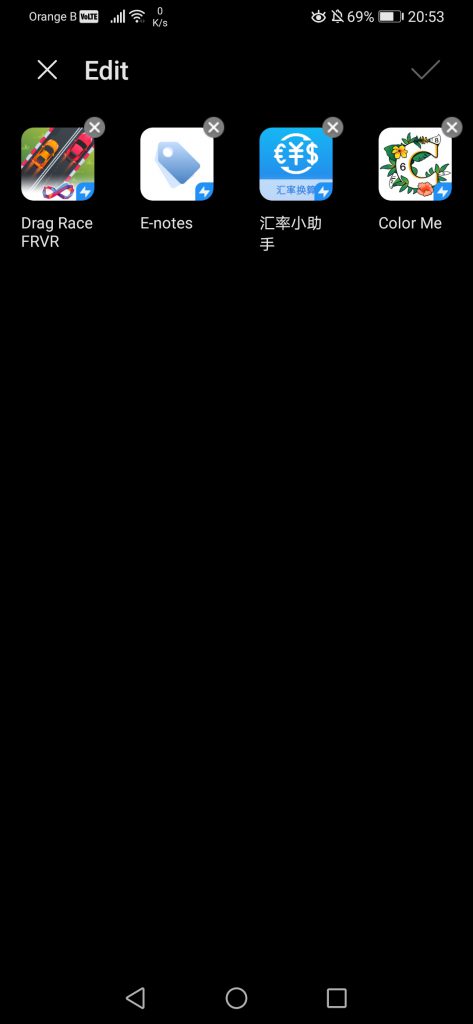

We’ve selected a few quick apps that have different functions. Recently used quick apps are listed when opening the Quick App Centre, and can even be favourited if need be, on top of added to the home screen.

Now, opening a quick app is easy, but performance seems to vary. While some open quickly and launch immediately, others will just load for a while, until we close them and reopen them again, which loads them instantly, which is curious. This is likely a temporary bug while Huawei irons out the service in Europe, and will be fixed down the line, but it remains a curious issue. The first application we’ll be looking at is a currency converter, which is in Chinese, although it is basic enough to understand how to use it:

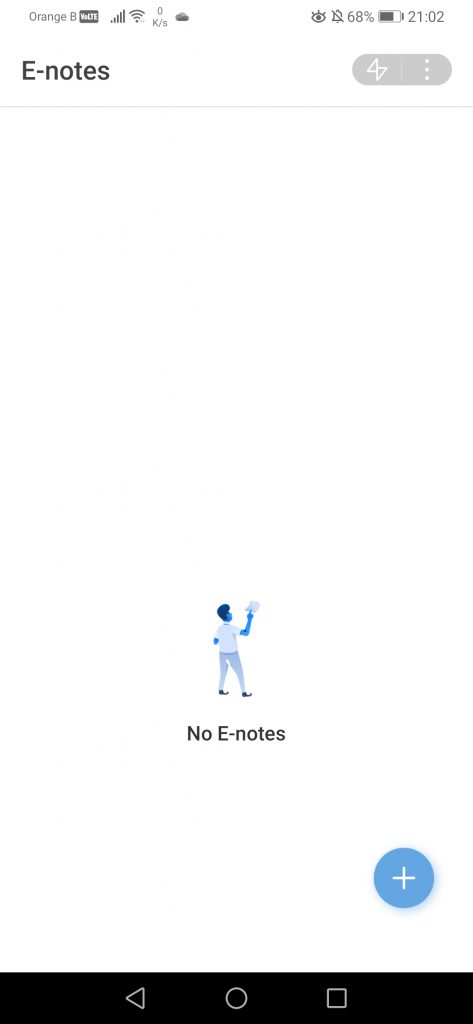

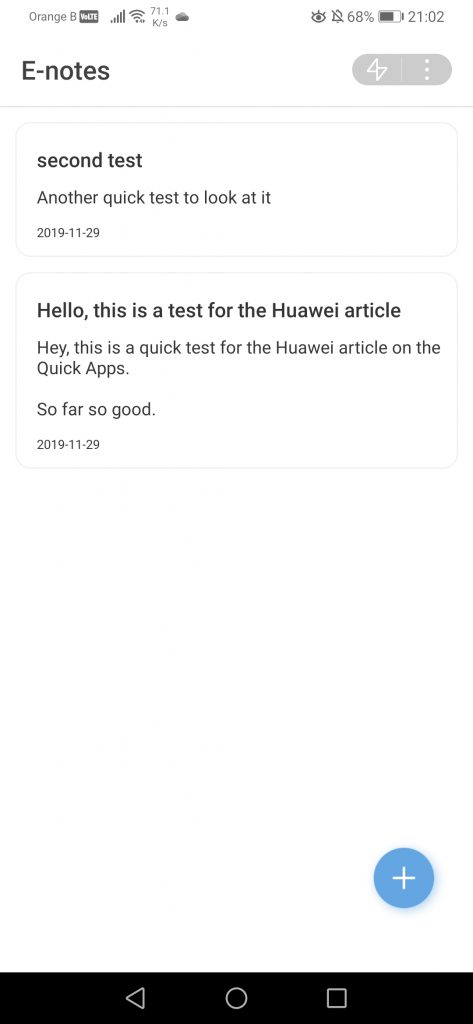

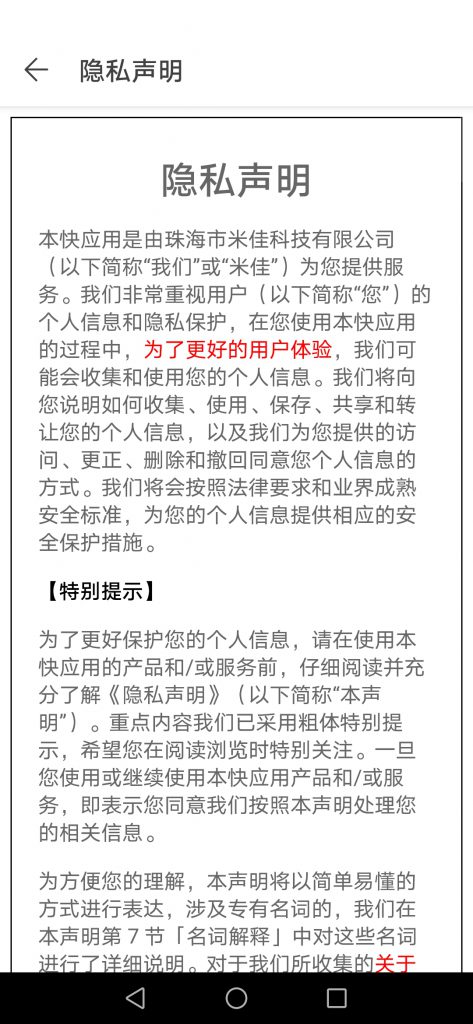

Next is an application to take notes, which is similar to Huawei’s Notepad, although more basic. The real question is why anybody would use this application when there’s one already pre-loaded on the device, that not only is more complete, but can also sync notes across multiple devices through a Huawei ID, as well as backing them to the Huawei Mobile Cloud, but maybe some users might prefer a different layout or a more basic, barebones notepad. Some improvements are still needed, as the application’s privacy policy is in Chinese, which is not ideal:

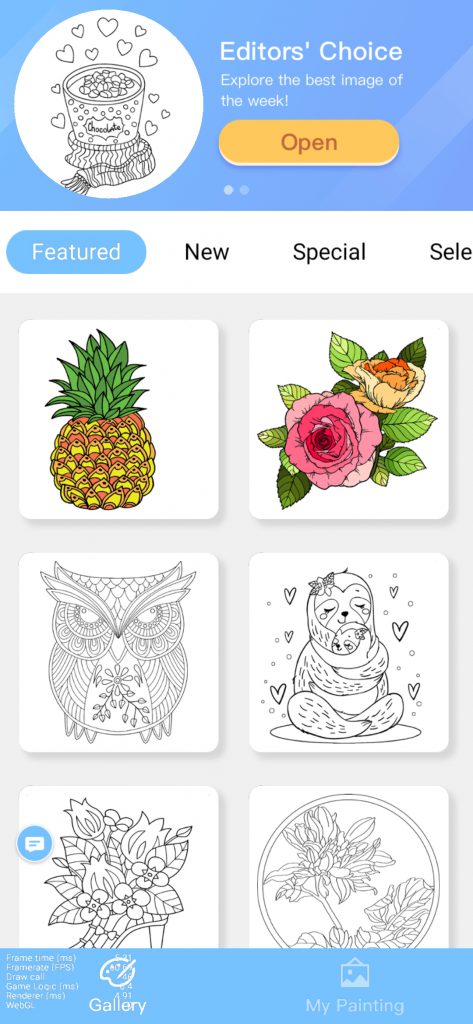

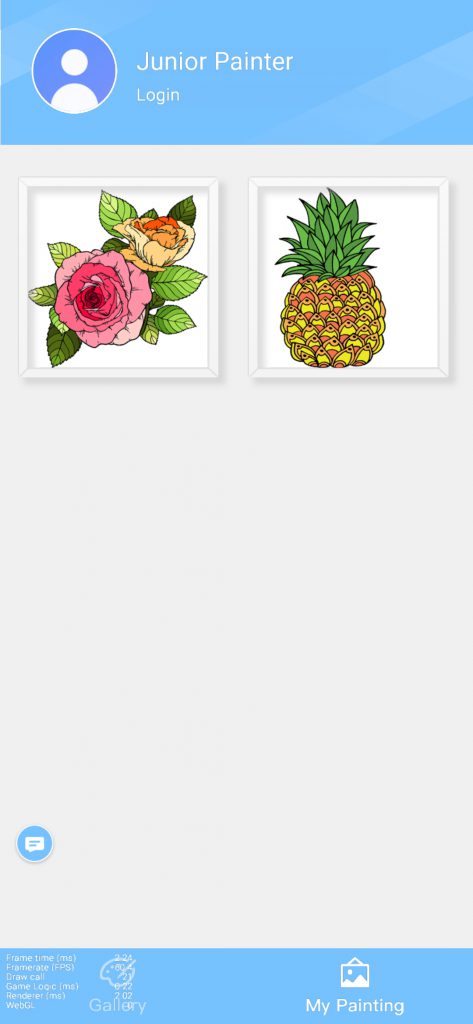

So far, we’ve only checked small, basic applications, and, as we can see, they work perfectly fine. We’ll now check out a more complex application, which, at least according to us, is the most interesting part of these “Quick Apps”: a game. Most users likely download a set of applications they use on a regular basis, such as messaging or banking apps, but games are something we install and uninstall regularly, especially seeing most games these days are quite basic, although addictive. Taking in account the restrictions imposed in terms of app size and others, we can see that the majority of quick app games available on Huawei’s Quick App Centre are games following the “Flappy Bird” design, essentially being very basic games with a repetitive gameplay but pushing the player to attempt to improve their score again and again. Of course, not all quick app games are like this, with the colouring application we are looking at being more complex. Please note that we’ve compressed the original video, meaning that what you see might not exactly match our experience:

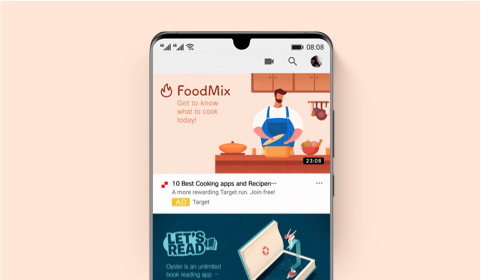

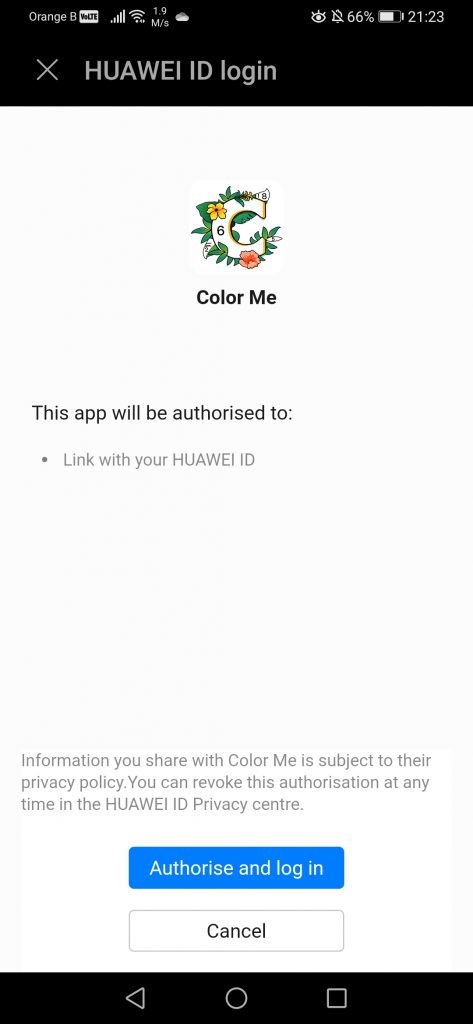

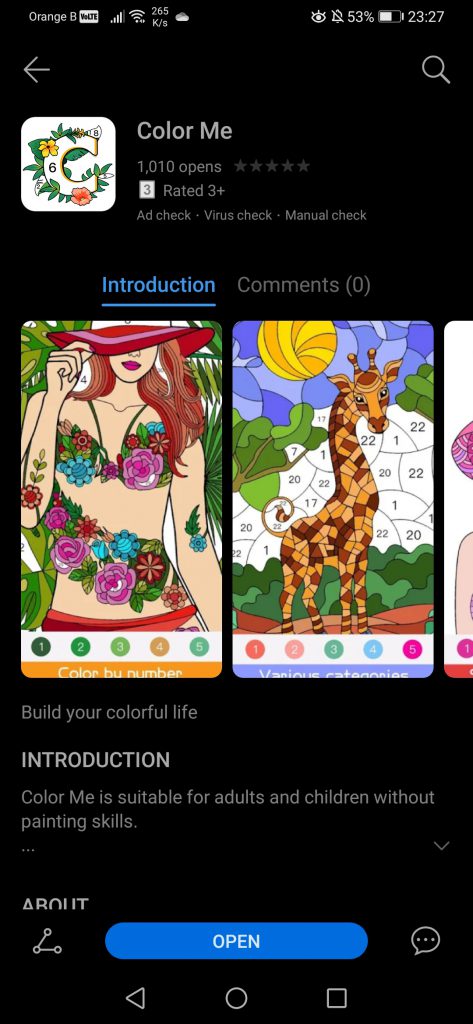

A lot can be said about this app. The performance overall is quite good, although there’s some loading here and there, but it remains fast enough as to not be annoying. The application allows users to save their drawing directly on the smartphone, but this means giving it permission to access our internal storage. It is also possible to login on the app with a Huawei ID to save the overall progress. Interestingly enough, the app also attempts to display advertisements from time to time, for tips or unlocking specific drawings, but it appears either the developer didn’t implement this yet, either they implemented it and it doesn’t work, or Huawei is still working on fixing this on their end.

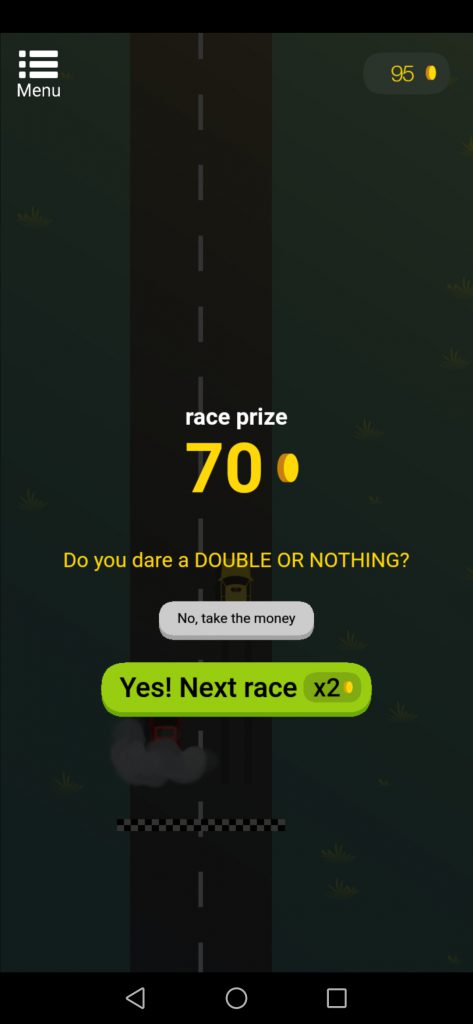

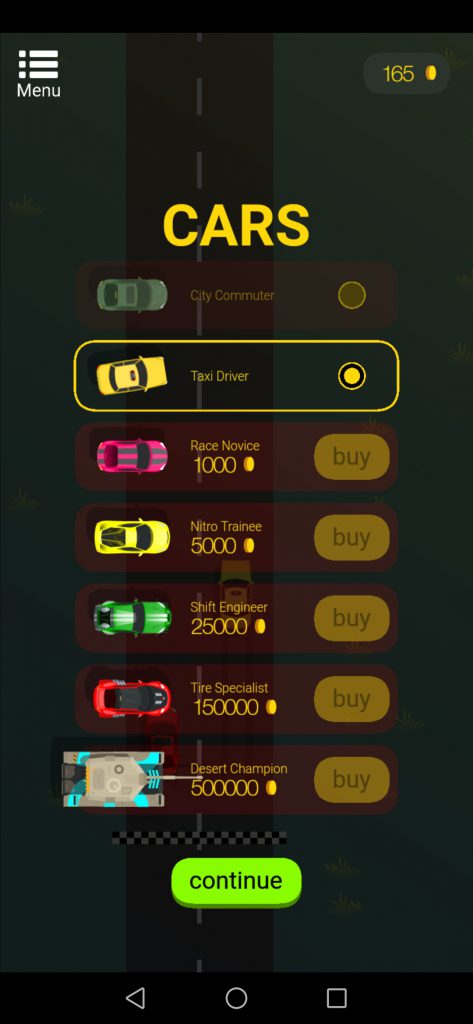

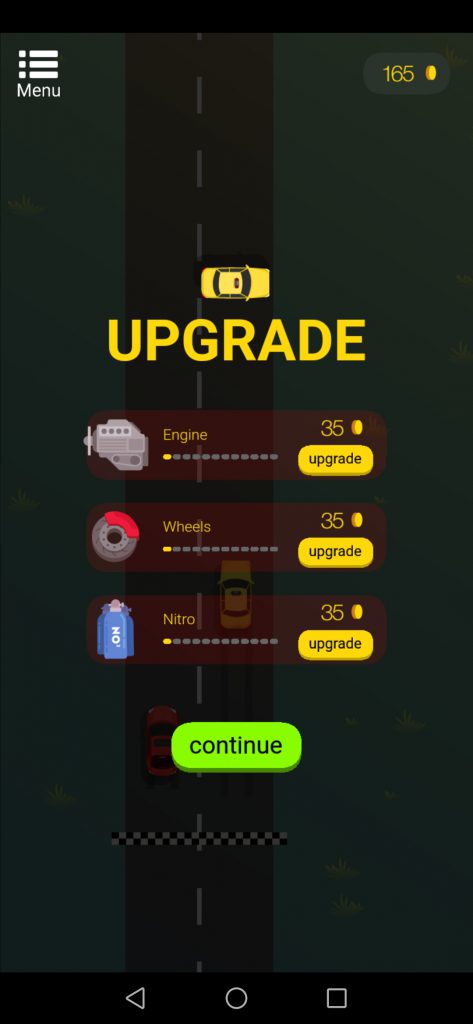

Ironically, the following game has ads that work properly, meaning the developer behind the colouring app made a mistake somewhere and did not properly implement the advertisements. This game follows the 2013 “Flappy bird” game design, as we’ve mentioned earlier, being an extremely simple car game with a repetitive yet addictive gameplay. The game also has sound and saves the progress:

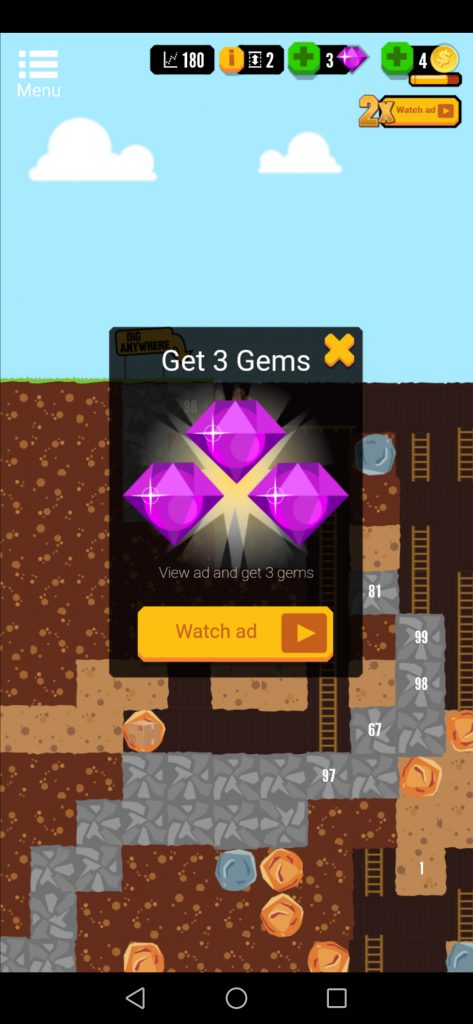

We then have a digging game, which also has integrated ads to obtain premium currency. An interesting thing to mention is how this application took longer to load due to us uploading the previous video to our servers, showing that a good internet connection is needed for these quick apps to properly load and work. Please note that we’ve compressed the original video, meaning that what you see might not exactly match our experience:

The last game we are checking out is again from the same developers, FRVR, who seem to be actively putting all their quick apps on Huawei’s service. This developer has quite a large collection of basic games covering quite a lot of different themes, such as tycoons, sports and even a “solitaire”-type card game. This last game we are looking at is some “puzzle” game, where players need to lay out parts in a specific way for the object to go from A to B. Usually this type of game uses water and pipes (the usual “plumbing” games), although in this case, it’s a train that has to go from A to B with a series of challenges, such as collecting coins:

Lastly, here’s how the Quick Apps look on the home screen, as well as opening them without needing to go through the Quick App Centre. If not for the logo on the corner, one wouldn’t be able to tell these are not applications installed on the device directly. The same can be said about Huawei’s global search feature, which finds the application when searching for this one, as mentioned in the company’s documentation, on top of listing it on Huawei AppGallery.

To end this article, we would like to point out the similarities between quick apps and a technology called “progressive web apps”, which are essentially websites with an optimized mobile experience, with their websites looking and feeling the same as a mobile application, although going through a browser. While this technology is interesting and extremely similar to quick apps, there are some differences between them, on top of the specific way the technology has been applied. For instance, while quick apps remain, at the end of the day, applications, websites are more limited in their direct interaction with the device. We also find quick apps to be faster and more fluid than websites optimized for mobile, likely due to the lack of direct, “visible” browser between them and the end user.

Both technologies have the same goal but have decided to do it in different ways. While one requires a [compatible] browser, which in itself is a negative point as it limits the choice of users in terms of browser variety, quick apps rely on smartphone manufacturers to be accessible, and, from the looks of it, even if quick apps share the same standard, they have to be submitted to each manufacturer individually, at least here in Europe. On the Chinese Quick App website, developers have to register through said website, then either link their existing developer account of each supported smartphone manufacturer, or sign up to a developer account with each manufacturer, which does make the process tedious, although the Quick App website then serves as a “unified” portal to upload, release and update Quick Apps. It will be interesting to see whether developers in Europe decide to adopt this technology and submit content, as well as whether Huawei and the other smartphone manufacturers will launch a similar option to the Chinese website Quick Apps, allowing developers to submit and update quick apps in an easier, more centralized way. It will also be interesting to see whether European users will test out and use this technology, as European and Chinese consumers do not behave the same way.

More on this subject: